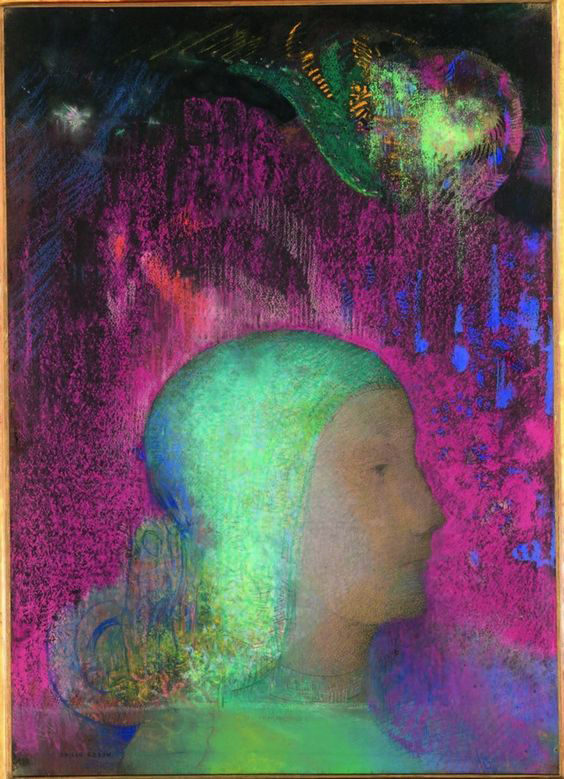

blue patches on the right, grouped together to form a nautilus shape, can be interpreted as a night sky, fireworks, or phosphenes, suggesting that the ‘background’, which moves towards the spectator, is really a representation of the figure’s inner mental space. The uncertainty about the scale and status of this representation is confirmed by the hooded figure beneath the nape of the female figure, coiled against a fold of her head-dress, which looks like an enormous serpent. The motif is a clear reminder of the figure of Death Redon visualized from Flaubert’s Tentation de Saint but its genetic relation to the profile remains enigmatic.

During his early years as an artist, Redon’s works were described as “a synthesis of nightmares and dreams”, as they contained dark, fantastical figures from the artist’s own imagination. His work represents an exploration of his internal feelings and psyche. He himself wanted to place “the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible”. A telling source of Redon’s inspiration and the forces behind his works can be found in his journal A Soi-même (To Myself). His process was explained best by himself when he said:

“I have often, as an exercise and as a sustenance, painted before an object down to the smallest accidents of its visual appearance; but the day left me sad and with an unsatiated thirst. The next day I let the other source run, that of imagination, through the recollection of the forms and I was then reassured and appeased.”

The mystery and the evocation of Redon’s drawings are described by Huysmans in the following passage:

“Those were the pictures bearing the signature: Odilon Redon. They held, between their gold-edged frames of unpolished pearwood, undreamed-of images: a Merovingian-type head, resting upon a cup; a bearded man, reminiscent both of a Buddhist priest and a public orator, touching an enormous cannon-ball with his finger; a spider with a human face lodged in the centre of its body. Then there were charcoal sketches which delved even deeper into the terrors of fever-ridden dreams. Here, on an enormous die, a melancholy eyelid winked; over there stretched dry and arid landscapes, calcinated plains, heaving and quaking ground, where volcanos erupted into rebellious clouds, under foul and murky skies; sometimes the subjects seemed to have been taken from the nightmarish dreams of science, and hark back to prehistoric times; monstrous flora bloomed on the rocks; everywhere, in among the erratic blocks and glacial mud, were figures whose simian appearance—heavy jawbone, protruding brows, receding forehead, and flattened skull top—recalled the ancestral head, the head of the first Quaternary Period, the head of man when he was still fructivorous and without speech, the contemporary of the mammoth, of the rhinoceros with septate nostrils, and of the giant bear. These drawings defied classification; unheeding, for the most part, of the limitations of painting, they ushered in a very special type of the fantastic, one born of sickness and delirium.”

The art historian Michael Gibson says that Redon began to want his works, even the ones darker in color and subject matter, to portray “the triumph of light over darkness.”

Redon described his work as ambiguous and undefinable:

“My drawings inspire, and are not to be defined. They place us, as does music, in the ambiguous realm of the undetermined.”

—Wikipedia

Back in his native Bordeaux, he took up sculpting, and Rodolphe Bresdin instructed him in etching and lithography. His artistic career was interrupted in 1870 when he was drafted to serve in the army in the Franco-Prussian War until its end in 1871.

At the end of the war, he moved to Paris and resumed working almost exclusively in charcoal and lithography. He called his visionary works, conceived in shades of black, his noirs. It was not until 1878 that his work gained any recognition with Guardian Spirit of the Waters; he published his first album of lithographs, titled Dans le Rêve, in 1879. Still, Redon remained relatively unknown until the appearance in 1884 of a cult novel by Joris-Karl Huysmans titled À rebours (Against Nature). The story featured a decadent aristocrat who collected Redon’s drawings.

In the 1890s pastel and oils became his favored media; he produced no more noirs after 1900. In 1899, he exhibited with the Nabis at Durand-Ruel’s.

Redon had a keen interest in Hindu and Buddhist religion and culture. The figure of the Buddha increasingly showed in his work. Influences of Japonism blended into his art, such as the painting The Death of the Buddha around 1899, The Buddha in 1906, Jacob and the Angel in 1905, and Vase with Japanese warrior in 1905, amongst many others.[4][5]

Baron Robert de Domecy (1867–1946) commissioned the artist in 1899 to create 17 decorative panels for the dining room of the Château de Domecy-sur-le-Vault near Sermizelles in Burgundy. Redon had created large decorative works for private residences in the past, but his compositions for the château de Domecy in 1900–1901 were his most radical compositions to that point and mark the transition from ornamental to abstract painting. The landscape details do not show a specific place or space. Only details of trees, twigs with leaves, and budding flowers in an endless horizon can be seen. The colours used are mostly yellow, grey, brown and light blue. The influence of the Japanese painting style found on folding screens byōbu is discernible in his choice of colours and the rectangular proportions of most of the up to 2.5 metres high panels. Fifteen of them are located today in the Musée d’Orsay, acquisitioned in 1988.

Domecy also commissioned Redon to paint portraits of his wife and their daughter Jeanne, two of which are in the collections of the Musée d’Orsay and the Getty Museum in California. Most of the paintings remained in the Domecy family collection until the 1960s.

In 1903 Redon was awarded the Legion of Honor. His popularity increased when a catalogue of etchings and lithographs was published by André Mellerio in 1913; that same year, he was given the largest single representation at the New York Armory Show, in Utica, New York.

Redon died on July 6, 1916.

—Wikipedia

***Beads strung on a chain, by themselves and beads simply added to wire or cord will not be accepted.***

Please add the tag or title JUN ABS to your photos. Include a short description, who created the art beads and a link to your blog, if you have one.

Monthly Challenge Recap

• From all the entries during the month, an editor will pick their favorite design to be featured every Friday here on the ABS, so get those entries in soon.